On February 13, 1960, the French military detonated the first of seventeen atomic bombs in the Algerian Sahara. The site of the inaugural bomb was Reggane—a district with a town, villages, and an oasis—located in the Tanezrouft Plain of the colonized desert, approximately 1,000 kilometers south of Algiers. Immediately after, General Charles de Gaulle, then President of the French Fifth Republic, made a public announcement: “Hurrah for France! As of this morning, it is stronger and prouder. From the bottom of my heart, my thanks to you and to those who have obtained for her this magnificent success.”1 France had thus entered into an exclusive nuclear weapons club, becoming the fourth country in the world to possess arms of mass destruction, after the United States of America, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, and the United Kingdom. De Gaulle’s pride was not affected by the destruction of human, animal, and vegetal lives, nor by the toxification of the hundreds of thousands of kilometers of natural, living, and built environments that these bombs caused over the following decades in Algeria and elsewhere.

Between February 1960—about five years after the outbreak of the Algerian Revolution and four years after the first exploitation of Algerian oil—and February 1966—around four years after Algeria’s independence from French colonial rule—France exploded four atmospheric and thirteen underground nuclear bombs in the Algerian Sahara. They also conducted tests of other nuclear technologies and weapons there, spreading radioactive fallout and causing irreversible contamination across Algeria, Central and West Africa, and the Mediterranean (including southern Europe). Up to this day, the facts and deeds of France’s nuclear weapons program in the Algerian Sahara remain a military secret. The majority of French institutional archives that document the production, detonation, and consequences of these weapons of mass destruction are classified and inaccessible to the public. This imposed amnesia not only encumbers the writing of France’s atomic histories in the Algerian Sahara, but also prevents victims, veterans, and civil groups from claiming the socio-economic, psychological, spatial, and health compensations and recognitions that should be accorded to them according to protocols of international law.

To covertly detonate its atomic weapons and to compete with other nations, the French army built two nuclear bases in the Sahara: the Centre saharien d’expérimentations militaires (CSEM, or Saharan Center for Military Experiments) in Reggane, and, about 600 kilometers southeast, in In Ecker, the Centre d’expérimentations militaires des oasis (CEMO, or the Center of Military Tests of Oases). CSEM included underground laboratories and workshops and was designed for about 10,000 civil and military French personnel, while CEMO was planned for approximately 2,000 civil employees and military French officials.2

Location of test sites. CEMO: Centre d’expérimentations militaires des oasis; CSEM: Centre saharien d’expérimenta- tions militaires. Source: International Atomic Energy Agency.

Map showing Reggane, the location of the CSEM, and the locations of the four Gerboise atmospheric nuclear tests and the pellet experiments. Source: International Atomic Energy Agency.

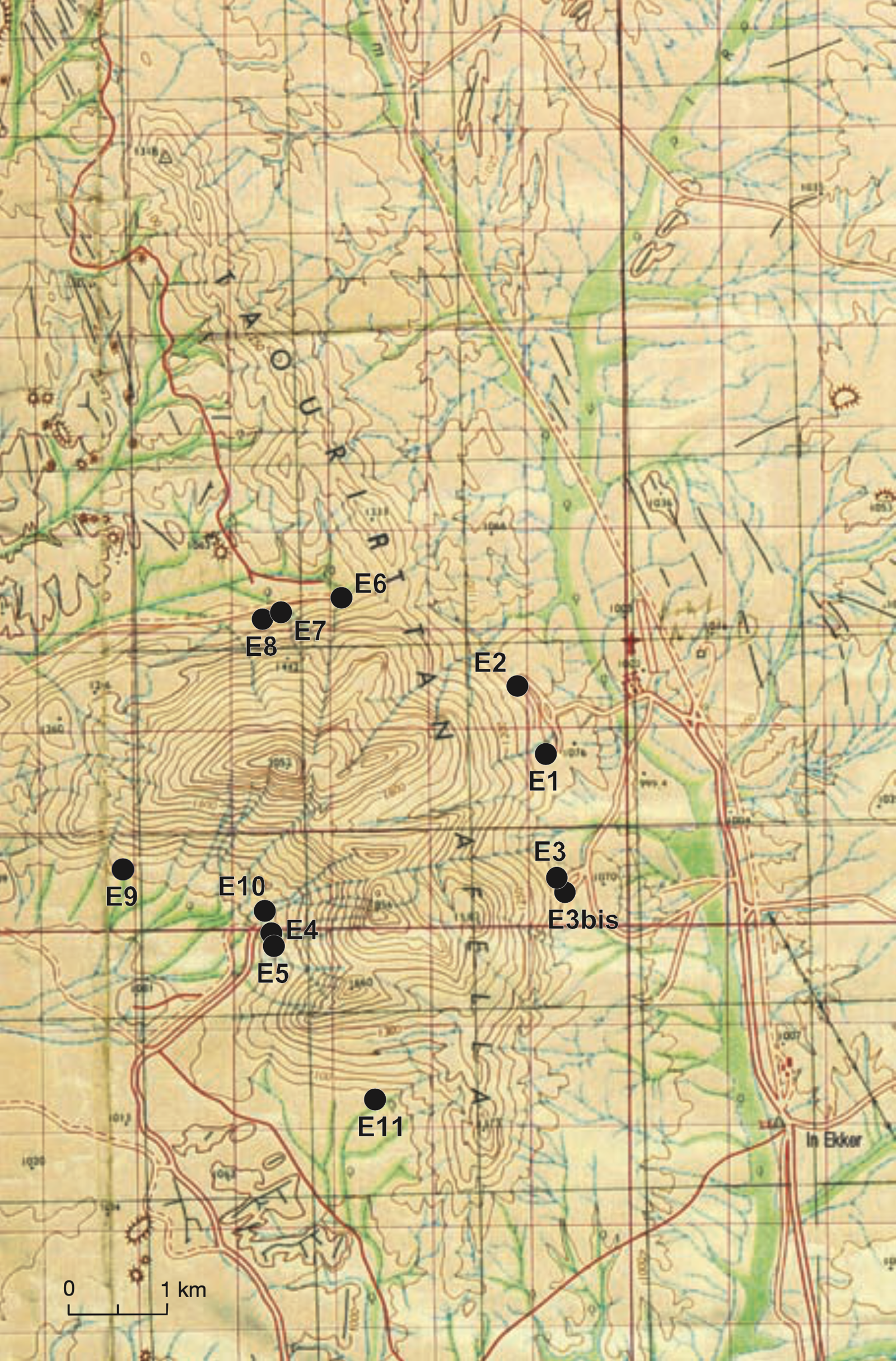

Map showing the locations of the tests in the Taourirt Tan Afella massif and near the Taourirt Tan Ataram massif (CEMO). Source: International Atomic Energy Agency.

Map showing the locations of the tunnel entrances for the underground tests in the Taourirt Tan Afella massif (CEMO). Source: International Atomic Energy Agency.

Location of test sites. CEMO: Centre d’expérimentations militaires des oasis; CSEM: Centre saharien d’expérimenta- tions militaires. Source: International Atomic Energy Agency.

Over an area of about 100,000 square kilometers, CSEM encompassed four geographic and functional zones that were connected by paved roads: 1) an existing Saharan town located near an oasis; 2) a new base-vie (residential base) called Reggane-Plateau; 3) a new advanced base (Hamoudia); and 4) a new zone des points zéro (“ground zero zone”), where the bombs were to be detonated. Whereas Reggane-Plateau was located about twelve kilometers east of Reggane-Ville, the shooting field was situated approximately fifteen kilometers south of the Hamoudia base and roughly fifty kilometers southwest of Reggane.3 By the spring of 1960, most of the construction of CSEM was nearly complete, comprising 82,000 square meters of buildings, 7,000 square meters of underground laboratories, 100 kilometers of roads, a water treatment facility capable of producing 1,200 cubic meters per day, 4,400 kilovolts of power spread across three power plants, more than 200 kilometers of underground cables and pipes, and 7,000 cubic meters of reinforced concrete in the ground zero zones.4

CEMO comprised a residential military base called Camp Saint-Laurent in northern In Amguel, thirty-five kilometers south of In Ecker. It also included an airbase located fifteen kilometers north of In Amguel, an advanced base (OASIS I) at the foot of the eastern flank of the Tan Afella massif for miners and other personnel, and an additional advanced base (OASIS II). OASIS I and II were both organized in four distinct zones: dwellings, offices, leisure and catering, and workshops. Between Camp Saint-Laurent and OASIS I was an existing French military base known as Bordj In-Eker, which at some point over the course of the twentieth century was extended and transformed into an advanced military base called the In Eker Military Camp.5

Whereas CSEM was designed for the detonation of atmospheric nuclear bombs above ground, CEMO was planned to facilitate the explosion of underground atomic bombs. The four atmospheric bombs detonated at CSEM were codenamed Gerboises (Jerboas) after the tiny jumping desert rodents. Gerboise Bleue (Blue Jerboa) was detonated on February 13, 1960; Gerboise Blanche (White Jerboa) on April 1, 1960; Gerboise Rouge (Red Jerboa) on December 27, 1960; and Gerboise Verte (Green Jerboa) on April 25, 1961. Whereas the colors in the name of the first three atmospheric bombs represented the French flag—blue, white, and red—the last three bombs formed the Algerian flag—white, red, and green.

However, since the colonization of Algeria in 1830, the French colonial regime had banned the presence of any Algerian flags in colonized Algeria. This is because France had claimed Algiers, Constantine, and Oran in the north of Algeria as French territories in 1848, while the French army had administered the Algerian Sahara in the south since 1902. At the time of the nuclear bombing tests, the colonial regime had for several years been fighting to suppress the Algerian Revolution and maintain its economic and political control of Algeria. The colors of the forbidden Algerian flag in the form of three nuclear weapons echoed and prolonged the longstanding French colonial violence in Algeria.

The thirteen underground atomic bombs detonated at CEMO, alternatively and accordingly, were codenamed after gemstones. Naming bombs after natural gemstones and animal life—jerboa—only further reiterates France’s colonial violence. Agathe was detonated on November 7, 1961; Béryl, on May 1, 1962; Émeraude, on March 18, 1963; Améthyste, on March 30, 1963; Rubis, on October 20, 1963; Opale, on February 14, 1964; Topaze, on June 15, 1964; Turquoise, on November 28, 1964; Saphir, on February 27, 1965; Jade, on May 30, 1965; Corindon, on October 1, 1965; Tourmaline, on December 1, 1965; and Grenat, on February 16, 1966. The yield of these underground atomic bombs ranged between 5–150 kilotons.6

The detonation of nuclear bombs at CEMO continued despite the approval of Algeria’s referendum on self-determination by 75% of French voters on January 8, 1961 and the ensuing independence from France in March 1962 after 132 years of French colonial rule.7 In 1966, France moved its nuclear weapons testing from Algeria to another territory under French rule: the Mururoa and Fangataufa atolls in colonized Ma’ohi Nui (so-called “French Polynesia”), in the southern Pacific Ocean. Despite objections and protests, the French colonial authorities conducted nearly 200 atmospheric and underground nuclear experiments there between 1966 and 1996, further toxifying colonized environments.8

The environmental and biological harm of French atmospheric and underground bombs in the Sahara was devastating and irreversible. In part, these catastrophic effects are linked to the radioactive matter that the Jerboas generated over the soil and sand of the Sahara. Like Trinity, the very first nuclear weapon that the United States detonated on July 16, 1945, in the so-called Jornada del Muerto Desert, New Mexico, the heat of the Jerboas’ explosions created a radioactive substance comprised of fused sand. Unlike “Trinitite,” the radioactive residue caused by Trinity bomb, however, the geologies that the Jerboas formed have not been named by anyone, and therefore have not been formally acknowledged. Not identifying and not naming the material and geological impacts of France’s first atmospheric bombs in the Sahara is part of a colonial project that undermines and silences the violent spatiality and the longstanding temporality of colonial toxicity. We may start, then, by naming this radioactive anthropogenic geology “Jerboasite.”

The four Jerboas bombs—Blue, White, Red, and Green—were detonated in the ground zero zone of CSEM. The first bomb, Blue, was a plutonium-filled bomb with a blast capacity of approximately 60 to 70 kilotons—roughly four times the strength of Little Boy, the atomic bomb dropped by the United States on Hiroshima in 1945.9 Blue, Red, and Green Jerboas were detonated atop a steel tower with an altitude ranging between 50 to 100 meters, whereas White Jerboa was detonated on the ground. The total explosive yield released in the four nuclear bombs was between 40 to 110 kilotons.10 The metal towers contained an elevator that allowed the bomb to reach the top and were surrounded by a metal fence and guarded by the French army. A self-guided device carried out the detonation of the bomb, which officials could watch at the control center thanks to cameras. The firing towers were completely destroyed by the blasts and heat of the explosion of each bomb.

In addition to the Jerboas, the French army conducted thirty-five experiments on plutonium pellets near the ground zero of Red Jerboa in April and May 1961, April 1962, and March, April, and May 1963. These experiments were designed to measure the velocity of a shockwave in a pellet of plutonium, each weighing between 24 to 30 grams. Some of these experiments were carried out in the atmosphere and others were performed in pits to limit dispersal. Regardless, not all of them were fully contained. Additional experiments, called Pollen— again obeying the same naming protocols as France’s colonial violence—were planned to simulate accidents involving plutonium and measure their consequences and impacts on the environment. These experiments were carried out about thirty kilometers southwest of Taourirt Tan Afella between May 1964 and March 1966, involving 20 to 200 grams of plutonium. After each Pollen test, the most contaminated areas were seemingly covered with asphalt to limit resuspension.11

In 1999, representatives of the Algerian government requested the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) carry out an expert mission and study the radiological situation at France’s former nuclear weapons testing sites in the Algerian Sahara. The IAEA’s special team was composed of experts from France, New Zealand, Slovenia, the United States, and the IAEA itself, which was supported by seven experts from the Algerian Commissariat à l’énergie atomique (Atomic Energy Commission). Over the course of an eight-day mission at both the Reggane and In Ekker sites, the team collected samples of sand, fused sand, solidified lava, vegetation, well water, and other materials to be analyzed in the IAEA’s laboratories in Seibersdorf, Austria.12 In their report, titled “Radiological Conditions at the Former French Nuclear Test Sites in Algeria: Preliminary Assessment and Recommendations,” published in 2005, six years after the mission, IAEA experts stated:

All sites in Reggane are contaminated. Gerboise Blanche and Gerboise Bleue are locally highly contaminated, with the most of the contamination residing in the black, vitreous and porous material (sand melted at the time of the explosion and then solidified). The unvitrified sand is much less active (100–1000 times less).13

The anthropogenic geology of Jerboasite covers a large part of the ground zero zone, as well as other parts of the Sahara due to wind and other exposures. One of the enduring impacts of France’s colonization of Algeria, these contaminated fragments pose a risk to human and nonhuman beings’ health and lives, as well as to their environments. The 1995 resolution of the General Conference of the IAEA calls on all states “to fulfil their responsibilities to ensure that sites where nuclear tests have been conducted are monitored scrupulously and to take appropriate steps to avoid adverse impacts on health, safety, and the environment as a consequence of such nuclear testing.”14 The French government is therefore accountable and responsible for the decontamination of its former nuclear weapons testing sites in the Sahara. Yet when will the French civil or military authorities clean the area, respecting the dignity of Saharan human and nonhuman lives?

The radioactive fused sand that is Jerboasite—or to use the IAEA’s description, “the black, vitreous and porous material”—featured in a 2008 documentary Vent de Sable: Le Sahara des essais nucleaire (Sand Wind: The Sahara of the Nuclear Tests), directed by Larbi Benchiha. Beyond documenting the construction of CSEM and its radioactive remains, the film also portrays an investigation conducted by Bruno Barillot, cofounder of the Observatoire des armements—a French independent non-profit center for expertise and documentation founded in 1984 in Lyon. In the documentary, Barillot states that this fused sand was clearly vitrified by the heat of the atomic explosions and incorporated matters contained in the bomb. Barillot mentions that, if and when this anthropogenic contaminated matter breaks, plutonium dust may be released, which is highly dangerous, and reminds viewers that the half-life of plutonium is approximately 24,400 years.15

In a 2014 article “Essais nucléaires français: à quand une véritable transparence?” (“French Nuclear Tests: When Will There Be Real Transparency?”), Barrillot denounced the French authorities’ ambiguity on its nuclear bombs and their radioactive consequences in the Algerian Sahara and on Saharan people and lives. He asks: “Is it not time now for complete transparency and for the French government to begin negotiations with the Algerian government on this painful page of the history of French-Algerian relations in order to agree on concrete actions of ‘rehabilitation’ and ‘reparation’?”16 It is not only time to implement the IAEA’s 1995 resolution “to take appropriate steps to avoid adverse impacts on health, safety and the environment,” but also to take immediate actions against the unrestricted circulation of the radioactive Jerboasite in the Algerian Sahara and elsewhere.

My translation. De Gaulle’s official remarks were circulated in press outlets, as cited in Serge Berstein and Pierre Milza, Histoire de la France Au XXe siècle (Paris: Editions Complexe, 1999), 315.

Bruno Barrillot, Les irradiés de la république: les victimes des essais nucléaires français prennent la parole (Bruxelles: Editions GRIP, 2003), 19–20.

Barrillot, Les irradiés de la république, 19–20.

“Rapport sur les essais nucléaires français 1960-1996, tome 1: La genèse de l’organisation et les expérimentations au Sahara CSEM et CEMO,” 46–47.

“Rapport sur les essais nucléaires français,” 129–38.

Barrillot, Les irradiés de la république, 55.

Barrillot, Les irradiés de la république, 55.

On the French atomic weapons tests in the southern Pacific Ocean, see, for example, Sébastien Philippe and Tomas Statius, Toxique: Enquête sur les essaies nucléaires française n Polynésie (Paris: PUF, 2021).

Charles Ailleret, L’aventure atomique française: Comment naquit la force de frappe. Souvenirs et réflexions (Paris: Editions Bernard Grasset, 1968), 382.

“Radiological Conditions at the Former French Nuclear Test Sites in Algeria: Preliminary Assessment and Recommendations: Radiological Assessment Reports” (Vienna: International Atomic Energy Agency, 2005), 7.

“Radiological Conditions at the Former French Nuclear Test Sites in Algeria,” 15, 16.

“Radiological Conditions at the Former French Nuclear Test Sites in Algeria,” 35.

“Radiological Conditions at the Former French Nuclear Test Sites in Algeria,” 1.

“Radiological Conditions at the Former French Nuclear Test Sites in Algeria,” 1.

The slightest dust of plutonium that settles in mucous membranes can radiate for ten or twenty years. Vent de Sable: Le Sahara des essais nucleaire (Sand Wind: The Sahara of the Nuclear Tests), directed by Larbi Benchiha, 2008.

Bruno Barrillot, “Visite du site d’essais français de Reggane au Sahara algérien: Observatoire des armements,” Damoclès, 2007, ➝

Half-Life is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Art Institute of Chicago within the context of its exhibition “Static Range” by Himali Singh Soin.